About a month ago we got our application approved for our solar hot water rebate through the Massachusetts CEC (a “quasi-public” organization). We were awarded $2425 for our solar hot water and monitoring systems. I was also hoping to apply for a Massachusetts zero interest HEAT loan, but those are, unfortunately, for existing construction.

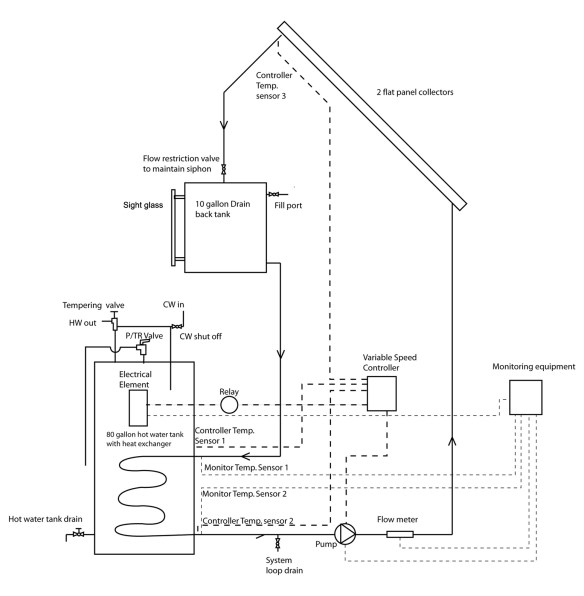

Our system:

Our equipment list:

- (2) Sun Earth EC-32 panels (now EC-40)

- Heat transfer products SuperStor Contender Solar 80 Gallon hot water tank with electric back up and internal heat exchanger

- AET 10 gallon drain-back tank

- Resol Deltasol BS Plus differential controller with variable pump speed control

- Sun Reports Apollo 1 monitoring system with Internet reporting

- Grundfos UPS 15-58 pump (with check valve removed)

- Grundfos VFS 2-40 flow-meter

On 7/29 our solar hot water panels, which we purchased through Northeast Solar of Hatfield MA, arrived. Good news bad news time.

Bad news: The wrong ones were delivered.

Good news: We were allowed to keep them.

What happened is Northeast Solar’s distributor delivered 4×10 panels instead of 4×8. Since they operate out of Cape Cod they weren’t about to drive back and forth to correct the matter. So we got an extra 16 square feet of panel for free! We weren’t sure at first if the panels would even work for us and we spent about 20 minutes of head scratching to make sure they would fit on our roof, which, subtracting the over-hang, is only 10.5 feet. In the end, as you can see in the photo below, the panels stick up several inches past the peak of the roof.

On 8/3, with the generous help of Dan and Ashley we mounted the panels on the roof without incident. The larger panels were certainly a challenge to lift though. Adam swears they weigh more than the 141 pounds that the SRCC data sheet claims.

Solar hot water panels mounted. Although it is not obvious in this picture, you can tell from the image below that the panels are not straight on the roof. This is no accident. This is a drain back system, where, if the sensor detects that it is too cold out, or there is no need for heat in the main tank, it automatically tells the pump to stop pumping. The water then drains back into the drain back tank. In my opinion, this type of "stagnation protection" technique is better than the more common use of pressurized antifreeze combined with a heat dump if there is too much heat in the system.